If we want to create content that resonates with young people, we have to start by listening to them

By Karen Ornat & Tobias Ebbrecht-Hartmann (The Hebrew University of Jerusalem)

When we set out to develop a social media concept for educating about the history of Nazi persecution, we knew one thing from the start: if we wanted to create content that resonated with young people, we had to start by listening to them. Not just observing online behavior or assuming their preferences—but genuinely engaging them in conversation.

Even though the development of the MEMORISE social media concept was informed from the outset by conversations with educators, historians, and digital media professionals, it really began to take shape when we sat down with German high school students aged 16 to 19. Through a series of focus group discussions, we explored how they use social media, how they encounter historical content online, and what kinds of formats, tones, and topics they find engaging—or off-putting. We showed them both existing examples of Holocaust-related videos and early MEMORISE pilot content, and asked for their candid reactions. Their insights became the foundation of the project, challenging us to think differently about how memory is communicated in the digital age. What followed was a set of nuanced and often surprising conversations that pushed us to rethink how Holocaust memory can be communicated to a generation that encounters history not just in books or classrooms, but often in brief, emotionally charged moments on their feeds.

Scrolling Between Entertainment and Education

Most of the students described TikTok and Instagram as their primary social media platforms. TikTok was associated with entertainment, humor, and spontaneous content. Instagram, by contrast, was seen as more curated and often used for seeing what friends were up to, news, and personal interests. YouTube was mentioned as a platform for longer, more serious content, but short-form video remained the dominant mode of engagement.

While the students described using social media primarily for entertainment, they spoke about regularly encountering content that taught them something—especially about politics, global events, or social justice. However, they did not always go searching for educational or informative content; instead, it often found them—woven into their daily feeds. This mode of learning aligns with what scholars have described as “incidental news,” where users come across news content not by intention, but through the flow of algorithmically curated, visually driven streams. For these students, the scroll itself had become a way of learning about the world—one that values emotional relevance, immediacy, and connection. Importantly, students drew a distinction between how they conceptualised social media—as primarily informal and entertainment-driven—and how they actually used it to learn about serious topics. While they viewed platforms like TikTok as spaces meant for light content, they also expressed appreciation for meaningful material when it appeared in ways that felt accessible and engaging.Reflections on Holocaust-Related Content

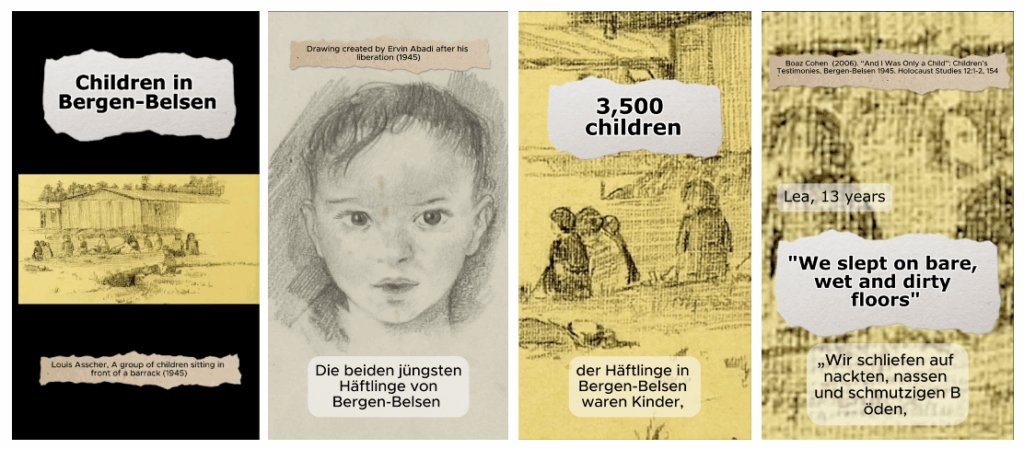

To generate concrete input for the MEMORISE concept, students were shown a range of Holocaust-related social media content. These included the internationally recognized Eva Stories project on Instagram, content from the Keine Erinnerungskultur account, and videos produced by the Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial. Each format sparked distinct responses and revealed different sets of preferences and concerns.Eva Stories

Reactions to Eva Stories were mixed. Some students appreciated its innovative use of Instagram Stories to present historical content in a familiar format. However, others felt that the dramatization and focus on using Instagram affordances such as selfies, hashtags, and polls undermined the gravity of the events depicted and was perceived by some as trivializing. A few noted that the stylized nature of the storytelling lacked sufficient context and could be confusing, especially for users unfamiliar with the background. While participants acknowledged the project’s success in reaching large audiences, they suggested that future content should strike a more careful balance between accessibility and authenticity.Keine Erinnerungskultur

The Keine Erinnerungskultur account received notably positive feedback. Students valued its personal tone, direct narratives, and the emotional engagement created through relatable storytelling. The connection between the speaker and real-life experiences—such as visiting a memorial—was particularly appreciated. Participants also liked the understated visual style and felt the content struck the right tone for social media: serious, thoughtful, and emotionally resonant without feeling overly produced or dramatized.Neuengamme Concentration Camp Memorial

Feedback on content from the Neuengamme Memorial was more ambivalent. While students greatly appreciated the effort to include underrepresented victim groups such as Sinti and Roma, they described some of the videos as too formal and visually static. The long shots of archival material and lack of a personal narrative were mentioned as barriers to emotional engagement. Several participants suggested that integrating diary excerpts, first-person testimonies, or presenters of similar age could help make the material more relatable.Recommendations for Content Development

Based on their engagement with existing content and pilot videos, the students made several recommendations that have directly informed the MEMORISE concept:

- Prioritise Relatable and Personal Narratives: Stories focused on people of a similar age, or experiences tied to school, friendships, and family life, were seen as especially impactful. There was also a call for content that highlighted everyday aspects of life in the camps to make the historical experience more tangible for younger viewers.

- Use Visually Engaging, Multi-Layered Formats: Short-form video content was consistently preferred, especially when paired with animations, text overlays, or archival imagery. Dynamic pacing was seen as key to holding attention.

- Balance Authenticity with Credibility: While polished, professional content was sometimes appreciated, it could also feel out of place on informal platforms. Students recommended a more casual tone and aesthetic—so long as it was paired with clear indicators of credibility, such as institutional logos or consistent branding.

- Avoid AI-Generated Content: There was broad consensus against the use of AI-generated images or voices. These were perceived as inauthentic and even unsettling, despite their increasing popularity on platforms like TikTok.

- Be Strategic with Influencers: While influencers could help extend the reach of Holocaust-related content, students emphasized that their engagement should feel meaningful and informed. Superficial collaborations were seen as potentially counterproductive.

- Ensure Quick Engagement: Several participants pointed out that if a video did not capture their attention in the first few seconds, they were unlikely to continue watching. A strong opening, both visually and emotionally, was considered essential.

- Always Include Subtitles: Most participants reported watching videos without sound, making subtitles not optional, but necessary.

Concluding Reflections

The findings from the focus group discussions and follow-up survey provide a clear roadmap for how Holocaust-related content can be adapted for today’s digital platforms. While students overwhelmingly valued authenticity, emotional connection, and historical accuracy, they also highlighted the constraints and expectations of the platforms they use daily. These constraints include short attention spans, algorithm-driven visibility, and the tension between entertainment and education. Importantly, 81% of survey respondents indicated that they believed social media could be an effective medium for learning about Nazi persecution. At the same time, 19% expressed skepticism—reminding us that the use of social media for historical education remains a contested and evolving space. Overall, the level of interest in the subject matter was high. A full 75% of participants expressed strong or moderate interest in Holocaust history, with particular attention to the personal experiences of victims, daily life in concentration camps, and the histories of lesser-known victim groups. While antisemitism and perpetrator narratives were mentioned less frequently, students called for more differentiation and the inclusion of marginalised perspectives. These insights have been central to the ongoing development of the MEMORISE social media concept, which aims to provide institutions with flexible, ethically grounded content strategies informed directly by the preferences and concerns of the young people they aim to reach.

To learn about the final social media concept, click here.Visit our social media guidelines.

References and more information can be found here:

Boczkowski, P., Mitchelstein, E., & Matassi, M. (2017). Incidental news: How young people consume news on social media. Proceedings of the 50th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. https://doi.org/10.24251/HICSS.2017.217]

Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T., & Divon, T. (2023). #DigitalMemorial(s): How COVID-19 reinforced Holocaust memorials and museums’ shift toward social media memory. In The COVID-19 Pandemic and Memory: Remembrance, commemoration, and archiving in crisis (pp. 267–294). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

Henig, L., & Ebbrecht-Hartmann, T. (2022). Witnessing Eva Stories: Media witnessing and self-inscription in social media memory. New Media & Society, 24(1), 202–226.

Literat, I., & Kligler-Vilenchik, N. (2019). Youth collective political expression on social media: The role of affordances and memetic dimensions for voicing political views. New Media & Society, 21(9), 1988–2009.

Manca, S. (2021). Bridging cultural studies and learning science: An investigation of social media use for Holocaust memory and education in the digital age. Review of Education, Pedagogy, and Cultural Studies, 43(3), 226–253.

Manca, S. (2021). Digital memory in the post-witness era: How Holocaust museums use social media as new memory ecologies. Information, 12(1), 31.

Swart, J. (2023). Tactics of news literacy: How young people access, evaluate, and engage with news on social media. New Media & Society, 25(3), 505–521.

Vázquez-Herrero, J., Negreira-Rey, M. C., & Sixto-García, J. (2022). Mind the gap! Journalism on social media and news consumption among young audiences. International Journal of Communication, 16, 21.

Walden, V. G. (2022). Understanding Holocaust memory and education in the digital age: Before and after COVID-19. Holocaust Studies, 28(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/17504902.2021.1979175

No responses yet